DELAWARE VALLEY POLICY, ARTS AND SPORTS COALITION PHILADELPHIA... FOR FRIENDS OF PHILLY

DO YOU HAVE FIRST PHILADELPHIAN FAMILY HISTORY?

TRAFFICKED BY BARGES AND BORDERED BY INDUSTRY, ARTS AND SPORTS

POLICY - DIVERSITY. EQUALITY. INCLUSION. JUSTICE

The Delaware River is still a working river. The river moves slow and hard supporting industry, providing jobs, carrying freight, sustaining agriculture, and transporting arts and sports leaders as far as near the cites of Philadelphia, Camden, West Chester, and Chester; with Cheltenham Township to be included.

The Delaware River may have an impact on the war on poverty if it moved a step further.

What would it take to move the river a step further: toward policy, the arts, sports, and waters near the cites of Philadelphia, Camden, and West Chester, Chester, and Cheltenham Township?

From its source in New York’s Catskill Mountains to its mouth in the Delaware Bay, the Delaware River serves many roles. Fifteen million people from four states (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware), including the communities of New York City and Philadelphia, drink its water.

We are a coalition of multi-ethnic groups - professional Indigenous people, professional Black people, professional White people, professional Asian people, professional Latin and Hispanic people, professional Caribbean people, religious and non-religious Jewish people, Young and Old people, and folks in general who are concerned about policy, arts and sports in areas of the Delaware Valley.

We are also taking interest in the several major cities that lie on the Delaware river and the Schuylkill River to help coalesce the Philadelphia area community. And we have formed a coalition to explore how the American colonies tied to the Philadelphia area community made formal social distinctions among its people and, even among people in the Philadelphia areas who weren't even its people, based on appearance, place of origin, nation, heredity and hierarchy.

The Delaware Valley area is a place for commerce, for wildlife, and, increasingly, even in its urban stretches, for fishing, kayaking, and other recreation.

Depending on which way Delawareans experience the river, you could hear all about the self-destruction of either the businesses or the people on the streets of Philadelphia.

Member-driven, selected, and multi-ethnic, momentum from the improving both river quality, as well as business and people quality involving Philadelphia has precipitated a new cadre of stakeholder groups— from boaters and anglers to environmental advocates and educators, to water utilities and regulators to policy advocates, arts advocates, and sports advocates, to recreation enthusiasts in Philadelphia, Camden, and elsewhere—to consider how to make the river and the city even healthier and more appealing to those that live within its watershed, near its banks, or nearby its neighborhoods.

That is the question driving a new coalition by friends interested in Delaware Valley policy, arts and sports: the creation of a revised roadmap for civics, registered voters running for any type of political office, social services that may have an impact involving friends of Philadelphia, and for quality of life improvements—grounded in science, grounded in the current state of the city.

By mobilizing relevant resources around a specific goal, the Delaware Valley Policy, Arts and Sports Coalition Philadelphia... for Friends of Philly offers the opportunity to coordinate services and limit duplication of parallel or competing efforts.

The coalition involves gathering and analyzing data about Philadelphia’s current

state and usages to envision what it would take to make the city safe for

“primary action; in other words: voter registration, voting, (voting involving political parties that make up government including but not limited to: advisory, local, state and federal), running for any political office in hopes of winning an election, types of policy, namely distributive, redistributive, regulatory and constituent in Business, Public Policy, Social Services, Case Studies and Political Theory, participation in the arts and sports.

There are various types of policy statements that each have their own style, scope, and purpose. These include human resources, financial, legal, safety, and operational policy statements; these five types of policies are the priorities of the Delaware Valley Policy, Arts and Sports Coalition Philadelphia.

Coalition Leadership. Coalition leadership requires attention to basic organizational functions - communication, clarity of roles, decision- making, etc. - just as in other organizations: these type of leadership functions are the priorities of the Delaware Valley Policy, Arts and Sports Coalition Philadelphia.

Coalition Advantages. The most common advantages are: • Potential for professional development • Improved communication on issues • Elimination of duplication • More readily available resources • Improved public image and communication • Better needs assessment: these type of advantages are the priorities of the Delaware Valley Policy, Arts and Sports Coalition Philadelphia.

- Public policy development.

- Agricultural policy.

- Cultural policy.

- Drug policy.

- Economic policy.

- Education policy.

- Foreign policy.

- Immigration policy

- Develop a one-to-one relationship with every coalition member.

- Resolve conflicts.

- Enlist members' active support.

- Comprehend each group's self-interests and help translate them into solid programs.

- Communicate positions on difficult, controversial issues.

The coalition wants to support continued improvements for both a river and city that can be accessible to thousands.

We are looking at the passage of policy, and improvements in terms of the quality of urban life and river-life that comes from great change. We like to be looking at what else we can do by addressing new quality of life and river-life concerns.

A city's need for transformation

By the early 1960's, Philadelphia's Philadelphia County caught poverty, extreme poverty (social exclusion and by an accumulation of insecurities in many areas of life: a lack of identity papers, unsafe housing, insufficient food, and a lack of access to health care and to education), loss of the arts and sports, as well as high crime and extreme crime, the result of intense situation poverty, generational poverty, absolute poverty, relative poverty, and urban poverty. Though not a new problem, public awareness of the poverty and crime helped usher in the enterprise zone and empowerment zone movement of the 1980s, including the creation of the Enterprise Zones in 1983, located in three areas: the American Street Corridor, Hunting Park West, West Parkside; the Port of Philadelphia enterprise zone was added in 1989.

By the early 1960's Philadelphia's Philadelphia County organizations and institutions offered black artists a platform from which to launch their careers and have a voice; the arts were being denied, especially to Black Philadelphians, all throughout the city. The curatorial framework is anchored between two significant historical events. In 1925 Philadelphian Alain Locke’s published "The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts," an important moment in the New Negro Arts Movement that issued a call to black American artists to find inspiration in their African heritage. In the 1970s, the nation’s bicentennial year, when American ideals of liberty and equality were being reconsidered in a contemporary context. Paintings, photographs, sculptures, and prints produced by black artists living and working in Philadelphia during the roughly 50 year period helped pave the way to make people more aware of crisis and art in the big city. Black Philadelphian art contributions to American art had largely been neglected.

By the early 60's, in Philadelphia's Philadelphia County it was much easier for Black athletes to make an impact in their respective fields, and there were plenty of trailblazers, nonetheless. The Negro Leagues provided an outlet for hundreds of talented baseball players who were then disallowed from suiting up for teams in Major League Baseball. Boxing was another sport where Black athletes excelled, with many famous Black boxers becoming world champions and fighting in some of the country's most storied venues. Yet it was not the athletic contests themselves that defined the changing nature of Philadelphia sports in the 1960s, but rather the way that developments in sports reflected the pressing societal issues of the era, from Cold War politics to civil rights to the widespread commercialization of Philadelphia culture. Some of the most pressing political issues of the 1960s affected the world of sports. Perhaps most pressing was the influence of the civil rights movement. When you think about Philadelphia’s history, most people think of battles and presidents, but sports is an important aspect of our city’s history. These were real people who had articles about their lives written telling stories of when they dealt with the issues of their day through sports; while other articles of their outfits represented poverty and the history of lynchings.

People in Philadelphia

Prior to the first waves of colonization, the major Pennsylvania Indian tribes were the Lenape, Susquehannock, Shawnee, Ojibwa, Blackfoot, Shawnee, and Iroquois.

Those original people of what would become the city of Philadelphia were the Lenape. They were hunters, fisher people, and cultivated the area around Philadelphia along the banks of what are now called the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers. The area was green and filled with rolling hills, verdant trees, wetlands, and a bursting ecological system.

The Lenape were divided into three sub-tribes: the Minsi (People of the Stone Country) inhabited the northern part of Pennsylvania, the Unami (People Who Live Down-River) inhabited the central region of Pennsylvania, and the Unalachtigo (People Who Live by the Ocean) inhabited the southern area of Pennsylvania.

Archeological evidence indicates that the Lenape inhabited the area centuries before the Europeans arrived. They established various villages along the Schuylkill River and its tributaries. Recent excavations in West Philadelphia reveal evidence of settlements along the west bank of the Schuylkill River along today’s Civic Center Boulevard.In 2001, a team of archeologist excavated the area prior to the building of a parking garage. During the excavation, numerous prehistoric artifacts were found, providing evidence of a fairly large and stable indigenous community occupying the area during the late archaic and early woodland periods, six thousand years ago.

In 1638, Dutch and Swedish colonizers, bought a tract of land from the Lenape near Wilmington Delaware, beginning a long history of transactions between the Lenape and the colonial powers. The first European to settle in the West Philadelphia area was a man named William Warner who arrived in 1677.

In 1682, William Penn arrived in the area to claim the lands guaranteed to him by the King of England, Charles II. The land was dedicated for persecuted Quakers but was already the homeland of the Lenape people. Penn, driven by the Quaker tenets of goodwill and friendship, was quick to establish treaty relations with the Lenape through the Shackamaxon agreement, that bought out their lands but allowed them to retain certain villages and locations, that could not be sold.

This all worked fine until the death of William Penn in the early 1700s.

His son, Thomas Penn, had no intention of holding to his father’s agreement and reinterpreted a 1686 accord with the Lenape as a new agreement called the Walking Purchase of 1737.

But it was no purchase, rather it was a devious plot to trick the Lenape into selling off almost a million acres of traditional land.

1763. Quaker and city leaders in Philadelphia, removed the Moravian Lenape, a group of Christian Lenape people living outside Philadelphia, to inside the city itself. As the mob of frontiersmen continued to grow and march on Philadelphia, Quaker people took up arms to defend their Lenape wards (and ostensibly, themselves). This is one of the few documented instances where Quakers chose to take arms to engage in combat, specifically on behalf of the Lenape people.

As with many eastern Nations, the subsequent centuries were not kind to the Native people of the Philadelphia area. Dispossessed of their lands and decimated by disease, the majority of Lenape migrated west with only a handful remaining in the area. However, many Native peoples continued trading in the city well into the 1800s.

As with most metropolitan areas, the Indigenous Peoples did not disappear but rather continued to work and live and establish new lives based on traditional culture. As of the 2010 Census, 13,000 residents of the city identified as Native American. Today, Lenape descendants, along with those of Cherokee, Navajo, Cree, Seminole, and Creek tribes, as well as many others, call Philadelphia home.

Above: Lenape

In 1995, a statue of Lenape Leader, Tamanend, was erected in the city. Located near the entrance of I-95 south commemorates the Native legacy in Philadelphia and the 1682 Treaty. The Tamanend is standing atop a turtle and is flanked by an eagle, the Lenape symbols of earth and sky and a tribute to the enduring legacy of the Lenape People.

Philadelphia in the early seventeenth century was an extremely difficult place to live, as there

were houses to build, fields to farm, and bitterly cold winters to face.

Children in this time had to grow up quickly and take on adult

responsibilities when they were as young as 16. Children were expected

to work, get married and become an adult member of society by this age; Philadelphia in the early twenty first century is also an extremely difficult place to live, as few own their houses, there are few fields to farm, and bitterly cold winters to face. Children today must grow up quickly and take on adult responsibilities when they are as young as 13. Children are expected to work, stay away from marriage but are encouraged to have sex and become an adult member of society by this age.

Together, in the years before 1800, Philadelphians organized almost all the essential institutions of the modern America that emerged in the nineteenth century. They created the country’s first banks, first insurance companies, and first stock exchange. The first daily newspaper, the first magazine, the first political cartoon, and the first public library. The first patent and the first trade show. The first turnpike and the first steamboat. The first non-sectarian college and the first university, and the first night school. The first hospital, the first medical school, and, maybe more tellingly, the first asylum for the insane. The first law firm and the first formal teaching of the law. The first labor organization and the first strike. The first protest against slavery, the first anti-slavery society, and the first independent African American church. The Army, the Navy, and the Marines, and for that matter the nation itself, and its first flag besides.

In the nineteenth century, Philadelphia claimed America’s first automobile, electric car, advertising agency, collegiate school of business, museums of science and of art, telephone, photograph, professional schools for women, books and magazines for the blind, municipal waterworks, Newman Club, rabbinic college, religious newspaper, YMCA, and more. In the twentieth century, it had the country’s first radio license, television station, modern skyscraper, airmail delivery, scientific management, black-owned-and-operated shopping center, computer, and more.

And the city birthed not only those great engines of progress but also inventions of delight: the nation’s first circus, balloon flight, merry-go-round, ice cream, soda (and then, inevitably, ice cream soda), pencil with eraser, Girl Scout cookie, western novel, bubble gum, zoo, movie, revolving door, Slinky, uniforms with numbers to identify players, and more.

By 1800, Friends were less than a tenth of its population – and Quakers

were never so modest. In William Penn’s portrait, he wore a gleaming

suit of armor. He turned to Quakerism to temper his pride and try to

turn it to love. And the non-Quaker majority was never modest either.

Ben Franklin expected that Philadelphia would become the capital of the

British Empire and that king and Parliament would in time relocate from

the Thames to the Delaware.

During the 1800s, Philadelphia led the nation in industrial production. There was a great expansion in mining, railroads and petroleum, iron and steel production. Manufacturing also grow, making Philadelphia an international industrial leader. This set the position for the city’s economic status and defined many international connections. During this time is when most of the neighborhoods and charity organizations were established.

By 1820, they did finally concede that New York might have more inhabitants, but they insisted that Philadelphia excelled its upstart rival in law, medicine, science, art, architecture, and every other amenity of cosmopolitan culture.

In the mid-late 19th century, Cantonese immigrants to Philadelphia opened laundries and restaurants in an area near Philadelphia's commercial wharves. This led to the start of Philadelphia's Chinatown.The first business was a laundry owned by Lee Fong at 913 Race Street; it opened in 1871. In the following years, Chinatown consisted of ethnic Chinese businesses clustered around the 900 block of Race Street. Before the mid-1960s it consisted of several restaurants and one grocery store.

In the mid-1960s, large numbers of families began moving to Chinatown. During various periods of urban renewal, starting in the 1960s, portions of Chinatown were razed for the construction of the Vine Street Expressway and the Pennsylvania Convention Center. The Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation was formed in 1968. This gave community and business leaders more say in matters of local development.

Up until the above-mentioned time period, all people in Philadelphia, a city in the United States, were known as the Delaware people who lived in and round about the City of Philadelphia and the County of Philadelphia.

European Settlement and 18th Century Estate Building in West Philadelphia

Many would like it to be believed that as a whole, there was a departure of the Lenape. However, facts are that the Lenape never departed the areas that would become known as the City of Philadelphia and the County of Philadelphia.

British farmers and craftsmen and later, Americans with substantial resources developed West Philadelphia. The first settlers typically built modest log and frame houses, but by the end of the 18th century large estates—with two-story brick and stone houses—had been developed along the banks of the Schuylkill River.

And it is very important to note that all the while the Lenape adapted to their European neighbors' building in the Philadelphia area; although there is a long debate about whether the European adapted to their Native American neighbors' building instead.

William Warner (ca. 1627-1707), a native of the parish of Blockley in Worcestershire, England, led the way.

Above: West Philadelphia - West Philadelphia detail of the 1752 map by N. Scull, G. Heap, and L. Hebert.

Warner is an important figure in the history of West Philadelphia. He arrived in the Delaware Valley in the mid-1670s and by 1677 had settled on the west bank of the Schuylkill River. It is said that he negotiated with the Lenape and purchased rights from them to 1,500 acres of land.

In any case, in the spring of 1678 he obtained from the Upland Court (located at present-day Chester, Pennsylvania) a formal order confirming his rights to 100 acres of land in West Philadelphia.

Two years later he obtained from the same court legal recognition of his rights to a contiguous tract of 200 acres, and in 1681, still another 400 acres.

When William Penn took control of Pennsylvania, Warner (and his family) patented a total of 588 acres with the new government.

The original farm of 300 acres fronted on the Schuylkill River in present-day Fairmount Park (at the site of Samuel Breck’s 1797 mansion house, "Sweetbriar") and stretched west, between narrow boundaries, as far as 60th and Media Streets. Warner named his farm "Blockley," after his birth place in England.

Warner was also a community leader in the first years of William Penn’s new colony. He sought election to public office and was rewarded with two terms in the Pennsylvania Assembly, the first in 1683 and the second in 1691. He was also a justice of the peace for Philadelphia County in 1685 and 1686. His influence proved lasting, for in 1705, when the entire 14.2 square mile area we know of as West Philadelphia today was first organized as a political entity, it was officially named Blockley Township. The Blockley name identified West Philadelphia for nearly 150 years.

Slavery in Philadelphia?

In Penn's new city of Philadelphia, African slaves were at work by 1684, and in rural Chester County by 1687.

William Penn was granted his colony in Pennsylvania in 1681, and added Delaware to it in 1682.

Though he flooded the "Holy Experiment" with Quakers whose descendants would later find their faith incompatible with slave-holding, the original Quakers had no qualms about it.

Penn himself owned slaves, and used them to work his estate, Pennsbury. He wrote that he preferred them to white indentured servants, "for then a man has them while they live."

In Penn's new city of Philadelphia, African slaves were at work by 1684, and in rural Chester County by 1687.

Between 1729 and 1758, Chester County had 104 slaves on 58 farms, with 70 percent of the slave owners likely Quakers.

By 1693, Africans were so numerous in the colony's capital that the Philadelphia Council complained of "the tumultuous gatherings of the Negroes in the town of Philadelphia."

In 1684, a ship named the Isabella anchored in Philadelphia’s port with approximately 150 captured Africans, which is considered the first shipment of enslaved Africans to arrive in the city after Penn’s arrival.

Except for the cargo of 150 slaves aboard the Isabella or the"Bristol"(1684), most black importation was a matter of small lots brought up from Barbados and Jamaica by local merchants who traded with the sugar islands.

Prominent Philadelphia Quaker families like the Carpenters, Dickinsons, Norrises, and Claypooles brought slaves to the colony in this way.

By 1700, one in 10 Philadelphians owned slaves. Slaves were used in the manufacturing sector, notably the iron works, and in shipbuilding.

Between 1718 and 1804, at least 10 vessels that participated in the trans-Atlantic slave trade docked in Pennsylvania ports carrying an estimated 1,000 enslaved Africans, according to the online database Slave Voyages.

Another 103 vessels carried more than 1,400 enslaved Africans from South America, the Caribbean and other American colonies to Pennsylvania between 1709 and 1776, according to the database.

Pennsylvania received deliveries of enslaved Africans primarily from the West Indies and Charleston, South Carolina, with shipments peaking between the late 1730s and 1750s, according to historians.

Blacks in Pennsylvania were sometimes referred to as “Guineas,” because they were taken from Africa’s Guinea coast, writes local historian Charles Blockson in “African Americans in Pennsylvania: A History and Guide.”

But by 1720, a wheat-based economy had sprung up, and the good reputation of Pennsylvania in Europe was luring Scots-Irish and German immigrants, who were willing to hire on as indentured servants in exchange for passage across the Atlantic. It's estimated that half the immigrants to colonial America arrived this way, and in Pennsylvania about 58,000 Germans and 16,500 Scots-Irish sailed up the Delaware between 1727 and 1754. The Quaker farmers turned to these for work on their farms. On a relatively small farm growing grain, it was cheaper to do it this way than to own slaves.

Indentured servitude was a long-term extension of the old English one-year hire for agricultural labor. Terms ranged from 1 to 17 years (children served the longest indentures), with a typical one being 4 or 5 years. The difference between indentured servants and slaves, on a day-to-day basis, was hard to define. During that time, the worker's labor, if not the worker himself, was a commodity that could be sold or traded or inherited, on the discretion of his owner. The discipline records of the Quaker meetings cover cases of members called to account for cruelty to indentured servants, and these tales tell of servants whipped, beaten and locked up for laziness.

Wars in the 1750s disrupted immigration patterns and cut down on the indentured servant pool. From 1749 to 1754, some 115 ships carrying almost 35,000 German immigrants reached Philadelphia. But in 1755-56 only three ships docked, and only one more arrived before 1763.[1] The French and Indian War also drew indentured male farm workers into the military.

The Quakers again began to buy slaves.

The importation of slaves into Philadelphia peaked 1759-1765.

Pennsylvania's slave population had risen gradually, from about 5,000 in 1721 to an estimated 11,000 in 1754. By 1766, it was believed to number 30,000. But the end of the French and Indian War opened up a fresh flood of European immigration. Slave importation fell off sharply.

Not only was colonial Pennsylvania a slave-owning society, but the lives of free blacks in the colony were controlled by law. The restrictions on slaves were mild, by Northern standards, but those on freemen were comparatively strict.

The restrictions had begun almost with the colony itself.

After 1700, when Pennsylvania was not yet 20 years old, blacks, free or slave, were tried in special courts, without the benefit of a jury.

Under other provisions of the 1725-26 act, free Negroes who married whites were to be sold into slavery for life; for mere fornication or adultery involving blacks and whites, the penalty for the black person was to be sold as a servant for seven years. Whites in such cases faced different or lighter punishment. The law effectively blocked marriage between the races in Pennsylvania, but fornication continued, as the state's burgeoning mulatto population attested.

The surrender of slavery was a minor disruption to most Pennsylvania Quakers' lives. Slavery in Pennsylvania had died of the market economy long before Quaker morality shifted against it. Despite the spike in the 1760s, there was never enough critical mass of slaveholding in Pennsylvania to produce a slave-based agricultural economy. In 1730, about one in 11 Pennsylvanians had been slaves; by 1779 the figure was no more than one in 30. The lack of a support structure by this time prevented it from catching on, even during the peak of slave importation.

The abolition bill was made more restrictive during the debates over it -- it originally freed daughters of slave women at 18, sons at 21. By the time it passed, it was upped to a flat 28. That meant it was possible for a Pennsylvania slave's daughter born in February 1780 to live her life in bondage, and if she had a child at 40, the child would remain a slave until 1848.[3] There's no record of this happening, but the "emancipation" law allowed it. It was, as the title of one article has it, “philanthropy at bargain prices.”

The 1780 abolition law actually had more immediate impact on the free blacks than the enslaved ones. The abolition of slavery was very gradual, while the restrictive laws on free blacks were lifted at once. The only rights of free whites that were not extended to them were those of voting and of serving in the state militia. There was actually some doubt about the voting, and on this point the act was interpreted differently in different places. In Philadelphia, blacks seemingly never voted. But in some of the western counties they did so in small numbers. York and Westmoreland were mentioned among these counties.

As New Englanders were doing, white Pennsylvanians then wrote slavery into their history in self-serving ways. John F. Watson's two-volume "Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time," published in several editions in the 1840s and '50s, was a widely read popular history of the state. The pages devoted to blacks and slavery, at the back of the second volume, begin with a description of the mildness of Pennsylvania slavery, then devote almost the whole of the text to the growth of abolition sentiment in the colony and the eventual end of slavery in the state, which is celebrated among its accomplishments.

"In the olden time domestic comforts were not

every day interrupted by the pride and profligacy of servants. The slaves of

Philadelphia were a happier class of people than the free blacks of the present

day generally are, who taint the very air by their vices, and exhibit every

sort of wretchedness and profligacy in their dwellings. The former felt

themselves to be an integral part of the family to which they belonged. They

experienced in all respects the same consideration and kindness as white

servants, and they were faithful and contented."

In 1780 there were about 6,855 slaves in the state, with some 539 in Philadelphia County.

In 1780, during the Revolutionary War, Pennsylvania became the first state to pass a law abolishing slavery.

Ten years later there were about 3,760 slaves in the state, or about 0.9% of the state’s population, and 301 in Philadelphia; free Blacks in the state numbered 6,537.

In the largest slave-holding state of South Carolina, enslaved Africans made up 43% of the population that year.

By the century's end, 1800, slavery was all but dead in Philadelphia, though it would linger in the state in ever declining numbers up to about 1847.

Not until 1854, when the City of Philadelphia expanded and incorporated all the townships in Philadelphia County, did a ward number substitute for Blockley as the designation for West Philadelphia.

Jews in Philadelphia

There are many ethnic groups of Jews.

Philadelphia has a story to tell about at least two key ethnic groups of Jews; the first group is the Sephardim Jews; the second group is the Ashkenazi Jews.

Jews in Philadelphia can trace their history back to Colonial America. Jews have lived in Philadelphia since the arrival of William Penn in 1682.

When did Sephardim Jews come to America?

Jewish traders have operated in southeastern Pennsylvania since at least the 1650s.

The first Jews that came to the New World were Sephardi Jews who arrived in New Amsterdam. Later major settlements of Jews would occur in New York, New England, and Pennsylvania.

Largely expelled from the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portuguese) in the late 15th century, Sephardim carried a distinctive Jewish diasporic identity with them to North Africa, including modern-day Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt; Southern Europe and Southeastern Europe, including France, Italy, Greece, Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovia, and North Macedonia; Western Asia, including Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Iran; as well as the Americas (although in smaller numbers compared to the Ashkenzi Jewish diaspora); and all other places of their exiled settlement.

They sometimes settled near existing Jewish communities, such as the one from former Kurdistan, or were the first in new frontiers, with their furthest reach via the Silk Road.

Historically, the vernacular languages of the Sephardim and their descendants have been variants of either Spanish or Portuguese, though they have also adopted and adapted other languages. The historical forms of Spanish that differing Sephardic communities spoke communally was related to the date of their departure from Iberia and their status at that time as either New Christians or Jews. Judaeo-Spanish, also called Ladino, is a Romance language derived from Old Spanish that was spoken by the eastern Sephardim who settled in the Eastern Mediteranean after their expulsion from Spain in 1492; Haketia (also known as "Tetouani" in Algeria), an Arabic-influenced variety of Judaeo-Spanish, was spoken by North African Sephardim who settled in the region after the 1492 Spanish expulsion.

When did Ashkenazi Jews come to America?

Beginning in the 1620s, many of the (Sephardic) Jews returned to Amsterdam (New York), having made enough money through trade to do so.

Returned from where?

Beginning in the 1620, many of the Jews, the Sephardic Jews, returned to Amsterdam from Africa.

These Jews were Black people(s) who were never slaves.

The possibility of living openly in the region as a Jew seems to have diminished by the 1630s, due to new, more pro-Portuguese rulers, meaning that the life span of these communities comprised some few decades at most (active Portuguese investigation of these communities commenced only in 1610).

Up until the 1630's, in America, there was no such identification for race as being non-White; because the race identity of being White didn't exist.

The term “race,” used infrequently before the 1500s, was used to identify groups of people with a kinship or group connection.

The modern-day use of the term “race” (identifying groups of people by physical traits, appearance, or characteristics) is a human invention.

During the 17th century, European Enlightenment philosophers’ based their ideas on the importance of secular reasoning, rationality, and scientific study, as opposed to faith-based religious understandings of the world.

Philosophers and naturalists were categorizing the world anew and extending such thinking to the people of the world.

These new beliefs, which evolved starting in the late 17th century and flourished through the late 18th century, argued that there were natural laws that governed the world and human beings.

Over centuries, the false notion that “white” people were inherently smarter, more capable, and more human than nonwhite people became accepted worldwide.

This categorization of people became a justification for European colonization and subsequent enslavement of people from Africa.

THE INVENTION OF RACE AND THE INVENTION OF HAVING A DUEL STATUS

The concept of “race” and "status" as we understand it today, evolved alongside the formation of the United States and was deeply connected with the evolution of four other terms, “white,” "nation," "black" and “slave.”

The words “race,” "status," “white,” "nation," "black" and “slave” were all used by Europeans in the 1500s, and they brought these words with them to North America.

However, the words did not have the meanings that they have today.

Instead, the needs of the developing American society would transform those words,’ (Race, Status, White, Nation, Black and Slave) with the addition of ("Peoples-Religion") meanings into new ideas.

One's religion was a person's status; or one's race was a person's status too; or one's religion and one's race became a duel status; or one's nation was a person's status; or one being white was a person's status; or being black was a status; or being a slave was a status. This was a new idea.

A significant turning point came in 1662 when Virginia enacted a law of

hereditary slavery, which meant the status of the mother determined the

what the status of the child was; also the status of being non-white may mean that the status of being black and the status of being a slave may mean once and the same thing.

This law deviated from English common law, which assigned the legal status of children based on their father’s legal status; this status was borrowed from the other groups that were identified as being non-white.

For example: Partus Sequitur Ventrem - In the colonies, this doctrine followed the colonists. Elizabeth Key, an enslaved, bi-racial woman sued for her freedom in Virginia on the basis that her father was white. The court granted freedom to her and her child in 1656.

Thus, children

of enslaved women would automatically share the legal status of “slave” but children of non-black women would never have the legal status of "slave."

This doctrine, partus sequitur ventrem, laid the foundation for the natural increase of the enslaved in the Americas and legitimized the exploitation of female slaves by white planters or other men and women.

But the fact is, the 1662 Virginia enacted law of hereditary slavery simply means, someone's non-white child may be a Slave; and anyone's non-white child may become a Slave; a non-black child may not be a Slave.

Therefore, in conclusion, although if a person's status was non-while, yet, if your father was white, regardless if they were born male or female, that person may no longer be excluded from being a slave.

Nevertheless, the 1662 Virginia enacted law of hereditary slavery, (which was a Colony Law not a British Law,) was an illegal law. The 1662 law of hereditary slavery was in violation of the laws of English Law of slavery.

Slavery in England was abolished by a general charter of emancipation in 1381.

No legislation was ever passed in England that legalized slavery, unlike the Portuguese Ordenações Manuelinas (1481–1514), the Dutch East India Company Ordinances (1622), and France's Code Noir (1685), and this caused confusion when English people brought home slaves they had legally purchased in the colonies.

In 1569, a man, Cartwright, was observed savagely beating another, which in law would have amounted to a battery, unless a defense could be mounted. Cartwright averred that the man was a slave whom he had brought to England from Russia, and thus such chastisement was not unlawful.

The case is reported by John Rushworth in his 1721 summary of John Lilburne's case of 1649. He wrote: "Whipping was painful and shameful, Flagellation for Slaves.

In the Eleventh of Elizabeth [i.e., 1569], one Cartwright brought a Slave from Russia, and would scourge him, for which he was questioned; and it was resolved, That England was too pure an Air for Slaves to breath in. And indeed it was often resolved, even in Star-Chamber, That no Gentleman was to be whip for any offense whatsoever; and his whipping was too severe."

It is reported that the court held that the man must be freed, and it is often said that the court held "that England was too pure an air for a slave to breathe in."

Subsequent citations claimed that the effect of the case was actually to impose limits on the physical punishment on slaves, rather than to express comment on legality of slavery generally. In the case of John Lilburne in 1649, the defendant's counsel relied upon Cartwright's case to show that the severity of a whipping received by Lilburne exceeded that permitted by law.

In none of subsequent common law cases prior to Somersett's case was Cartwright's case cited as authority for the proposition that slavery was unlawful.

It is inferred that, because he was from Russia, Cartwright's slave was white, and probably a Christian, although this is not recorded.

However, it is possible that he was African, as, although they were

uncommon, African slaves in Russia were not unknown prior to the

emergence of the Atlantic Slave Trade.

Slavery was not illegal in Britain if an individual was a merchant or if individual was doing slavery involved in the merchant business of mercantile law.

However, those disputes predominantly concerned disputes between slave merchants (the notable exception being Shanley v Harvey, as to which see below), for whom it would have been commercially unwise to plead that slavery was unlawful.

In 1667, the last of the religious conditions that placed limits on servitude was erased by another Virginia law. This new law deemed it legal to keep enslaved people in bondage even if they converted to Christianity.

However, converting to Christianity really didn't matter; because the Jews as well as many other religious groups had Slaves too.

There were some religions, such as Islam for example, that didn't follow the new law that deemed it legal to keep enslaved people in bondage even if they converted to the slave owner's religion.

In 1677, after the Royal African Company went bankrupt, the high court of King's Bench intervened to change the legal rationale for slavery from feudal law (feudalism) to the law of property (proprietiesism).

Feudalism helped protect communities from the violence and warfare that broke out after the fall of Rome and the collapse of strong central government in Western Europe. Feudalism secured Western Europe's society and kept out powerful invaders. Feudalism helped restore trade.

Proprietiesism helped to protect communities committing violence and warfare that broke out after the beginning of the 13 Colonies and the building of strong central government in America.

In England, in 1677 in Butts v. Penny the courts held that an action for trover (a kind of trespass) would lie for black people, as if they were chattels or equal to being goods.

The rationale was that infidels could not be subjects because they could not swear an oath of allegiance to make them so (as determined in Calvin's Case in 1608).

As aliens, they could be considered as "goods" rather than people for purposes of trade.

However, Chief Justice Holt rejected such a status for people in Harvey v. Chamberlain in 1696, and also denied the possibility of bringing an assumpsit (another kind of trespass) on the sale of a black person in England: "as soon as a negro comes to England he is free; one may be a villein in England, but not a slave."

It is alleged that he commented as an aside in one case that the supposed owner could amend his declaration to state that a deed was created for the sale in the royal colony of Virginia, where slavery was recognized by colonial law, but such a claim goes against the main finding in the case.

In 1706 Chief Justice Holt refused an action of trover in relation to a slave, holding that no man could have property in another, but held that an alternative action, trespass quare captivum suum cepit, might be available.

Ultimately the Holt court decisions had little long-term effect. Slaves were regularly bought and sold on the Liverpool and London markets, and actions on contract concerning slaves were common in the 18th century without any serious suggestion that they were void for illegality,

In 1700 there was no extensive use of slave labor in England as in the colonies. African servants were common as status symbols, but their treatment was not comparable to that of plantation slaves in the colonies.

The legal problems that were most likely to arise in England were if a slave were to escape in transit, or if a slave-owner from the colonies brought over a slave and expected to continue exercising his power to prevent the slave from leaving his service.

Increasing numbers of slaves were brought into England in the 18th century, and this may help to explain the growing awareness of the problems presented by the existence of slavery.

Quite apart from the moral considerations, there was an obvious conflict between defining property in slaves and an alternative English tradition of freedom protected by habeas corpus.

If the courts acknowledged the property which was generally assumed to exist in slaves in the colonies, how would such property rights be treated if a slave was subsequently brought to England?

In 1771 Slavery in Britain was a crime punishable up to imprisonment or even death

One of the few non-commercial disputes relating to slavery arose in R v Stapylton (1771, unreported) in which Lord Mansfield sat. Stapylton was charged after attempting to forcibly deport his purported slave, Thomas Lewis. Stapylton's defence rested on the basis that as Lewis was his slave, his actions were lawful.

Lord Mansfield had the opportunity to use a legal procedure at the time in criminal cases referred to as the Twelve Judges to determine points of law (which were not for the jury) in criminal matters. However, he shied away from doing so, and sought (unsuccessfully) to dissuade the parties from using the legality of slavery as the basis of the defense.

In the end Mansfield directed the jury that they should presume Lewis was a free man, unless Stapylton was able to prove otherwise. He further directed the jury that unless they found that Stapylton was the legal owner of Lewis "you will find the Defendant guilty". Lewis was permitted to testify.

The jury convicted.

However, in the course of his summing up, Lord Mansfield was careful to say "whether they [slave owners] have this kind of property or not in England has never been solemnly determined.

With the decree of the 1662 Colony Law for the purpose of war for slavery, and the long standing 1300's Britain Law for the purpose of war against slavery, the justification for black servitude

in the Colonies changed from a religious status to a designation based on "race status” "nation status," "white status" or "black status."

The status of Slavery, Race, Nation, White and Black, according to the Colony Law of 1662 is the main reason why the American Revolution started on April 19, 1775; with the exchange of gunfire at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts.

In late November or early December 1781 the captain and crew of the English slave ship, Zong, threw various African slaves into the sea off the island of Hispaniola, to save the lives of the remaining slaves as provisions were short.

The shipowners then sought to claim under policies of insurance, arguing that jettisoning the cargo constituted a recoverable loss, even though it necessarily resulted in the murder of the slaves. In the first round of legal proceedings a jury initially held for the shipowners and upheld the claim.

On a subsequent application to set that judgment aside, Lord Mansfield indicated that the jury in the initial trial "had no doubt (though it shocks one very much) that the Case of Slaves was the same as if horses had been thrown over board". That finding was overturned and fresh trial ordered, but in both legal actions it was accepted in principle by the court that the killing of the negro slaves was permissible, and did not thereby invalidate the insurance by virtue of being an unlawful act.

Shortly afterwards provisions in the Slave Trade Act 1788 made it unlawful to insure against similar losses of slaves.

In 1811, Arthur Hodge became the first (and only) British subject ever to stand trial for the murder of a slave. As part of his defense, Hodge argued that "A Negro being property, it was no greater offense for his master to kill him than it would be to kill his dog," but the court did not accept the submission, and point was dismissed summarily.

Counsel for the prosecution also obliquely referred to the Amerlioration Act 1798 passed by the Legislature of the Leeward Islands, which applied in the British Virgin Islands. That Act provided for penalties for slave owners who inflicted cruel

or unusual punishments on their slaves, but it only provides for fines,

and does not expressly indicate that a slave owner could be guilty of a

greater crime such as murder or another offense against the person.

The trial took place under English common law in British Virgin Islands.

However, there was no appeal (Hodge was executed a mere eight days after the jury handed down their verdict). The jury (composed largely of slave owners) actually recommended mercy, but the court nonetheless sentenced Hodge to death, and so the directions of the trial judge are not treated by commentators as an authoritative precedent.

The common law, ultimately, would go no further. But the decision of 1772 in James Somersett's case was widely misunderstood as freeing slaves in England, and whilst not legally accurate, this perception was fueled by the growing abolitionist movement, notwithstanding this was scarcely an accurate reflection of the decision.

Slavery did not, like villeinage, die naturally from adverse public opinion, because vested mercantile interests were too valuable.

In 1788 the Slave Trade Act 1788 was passed, partly in response to the Zong Massacre to ameliorate the conditions under which slaves might be transported (the Act would be renewed several times before being made permanent in 1799).

In 1792 the House of Commons voted in favor of "gradual" abolition, and in 1807 parliament outlawed the African slave trade by legislation. This prevented British merchants exporting any more people from Africa, but it did not alter the status of the several million existing slaves, and the courts continued to recognize colonial slavery.

The abolitionists therefore turned their attention to the emancipation of West Indian slaves. Legally, this was difficult to achieve, since it required the compulsory divesting of private property; but it was finally done in 1833, at a cost of £20 million paid from public funds to compulsorily purchase slaves from their owners and then manumit them. Freed slaves themselves received no compensation for their forced labor. From 1 August 1834, all slaves in the British colonies were "absolutely and forever manumitted."

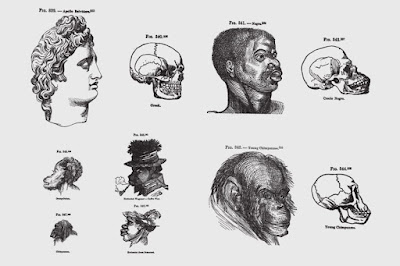

In the mid-19th century, science and the scientific community served to legitimize society’s racist views.

Scientists argued that Africans and their descendants were inferior (meaning every group of people who are categorized as being non-white) - either a degenerate type of being or a completely separate type of being altogether, suitable for perpetual service.

Like the European scholars before them, American intellectuals organized humans by category, seeking differences between racial populations.

The work of Dr. Samuel Morton is infamous for his measurements of skulls across populations. He concluded that African people had smaller skulls and were therefore not as intelligent as others. Morton’s work was built on by scientists such as Josiah Nott and Louis Agassiz. Both Nott and Agassiz concluded that Africans were a separate species. This information spread into popular thought and culture and served to dehumanize African-descended people further while fueling anti-black sentiment.

"Types of mankind or ethnological researches, based upon the ancient monuments, paintings, sculptures, and crania of races, and upon their natural, geographical, philological, and biblical history" (Nott, Gliddon, 1854) (J.C. Nott and Geo. R. Gliddon/Google Books). License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

By the 1850s, antislavery sentiment grew intense, in part, spurred by white Southerner’s aggressive attempts to protect slavery, maintain national political dominance and to spread the “peculiar institution” to newly acquired American lands.

Pro slavery spokespeople defended their position by debasing the value of humanity in the people they held as property. They supported much of this crusade through the racist scientific findings of people like Samuel Morton, which was used to argue the inferiority of people of African descent.

As the tension between America’s notion of freedom and equality collided with the reality of millions of enslaved people, new layers to the meaning of race were created as the federal government sought to outline precisely what rights black people in the nation could have.

It was in this philosophical atmosphere that the Supreme Court heard one of the landmark cases of U.S. history, the Dred Scott v. Sanford. Dred Scott and his wife claimed freedom on the basis that they had resided in a free state and were therefore now free persons.

The Supreme Court ruled that Scott could not bring a suit in federal court because Black people were not citizens in the eyes of the U.S. Constitution. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney also ruled that slaves were property based on the Constitution, and therefore owners could not be deprived of their property.

Ultimately, Taney declared with the full force of law that to be black in America was to be an “inferior being” with “no rights” which the white man was bound to respect,” and that slavery was for his benefit. Taney used the racist logic of black inferiority that saturated American culture of the time to argue that African descents were of another “unfit” race, and therefore improved by the condition of slavery.

The court’s racist decision and affirmation that African descendants were mere property would severely harm the cause of black equality and contribute to anti-black sentiment for generations to come.

The openness that made functional sense within and took advantage of the religious freedom along the West African coast led to a strong backlash in Amsterdam in the form of a series of ascamot excluding blacks and mulattos from or restricting them within Jewish communal life there also.

Basically then, Amsterdam was Philadelphia and Philadelphia and all the surrounding areas of the Delaware Valley was Amsterdam; what happened to the people in Amsterdam involving non-whites happened to the people in Philadelphia.

This decades-long racially-based exclusionary campaign, which spread beyond Amsterdam to other Sephardic communities in the Caribbean, is dialectically related to patterns in West Africa; it is part of the same story. Local specification do not negate regional or cis-atlantic patterns; both must be taken into account.

The backlash in Amsterdam against the Africans and mixed-race individuals is palpable. It likely reflects the difference between the relatively open Portuguese attitude toward race and race-mixing and the seemingly more disinterested Dutch approach, as well as between colony and metropole.

Treating seventeenth-century phenomena, Davis offers a powerful depiction of the imagined and discursive place of slavery in Sephardic colonization.

She speculates that the fact that so many African male slaves arrived circumcised “must have eased the worry of those Jews [in Dutch Brazil] who took seriously the biblical and halakhic requirement of circumcision.”

In a noteworthy find, she discovered that Amsterdam Rabbi David Pardo recommended in his 1689 Spanish-language survey of laws Sephardic Jews should follow that plantation owners, in order to “complete” the African circumcisions of their slaves, need merely take a drop of blood, as halakhically required.

A wonderful micro-study of David Nassy (also spelled Nassi), perhaps the elite Portuguese Jewish planter best known to scholars, reveals him expressing the sentiments typical of an ameliorationist. As late as 1795, after three years in Philadelphia and even in the company of mostly Quaker abolitionists, he denied liberty and equality to Blacks, since, he felt, being uncivilized, they would only serve as negative temptations.

Yet he urged masters not to mete out “horrible punishments” to their slaves, but rather offer proper care, in order to prolong their lives and increase their birth rate.

While proper care for slaves in a cruel slave society reflected a call for humane treatment, his concern for slaves’ birth rate evinces a concern for the master’s commercial well-being: more slaves, being his property, means more bodies available for labor or profitable sale. These attitudes informed his demeanor toward the mixed-race Jews in the Portuguese Jewish community.

The Enlightenment-influenced Nassy’s 1789 reforms of the ascamot, intended to modernize the community’s self-governance, made no changes to the rules that kept mixed-race individuals as lesser congreganten and not full members, jehidim, while also insisting on humiliating seating arrangements for them in synagogue.

Yet on a personal level, as an owner of slaves and as plantation owner for a time, in the 1770s Nassy treated his slaves relatively well. Three mulatto slaves, Moses, Ishmael, and Isaac, were all circumcised, brought into Judaism and eventually manumitted.

A medical man, Nassy tended to the skin disease of the young slave Mattheus, carpenter and personal attendant, whom he rented and then purchased, looking out for him in general due to Mattheus’s good service and loyalty.

During his three years in Philadelphia, from 1792, he came to know the two Quaker-connected, pro-abolitionist Jews at the Mikveh Israel congregation. Nassy freed Mattheus and his own daughter Sarah’s ten-year-old slave girl Amina in Philadelphia, maintaining them both as indentured servants for the next seven years in Mattheus’s case and eighteen years in the girl’s case.

While these acts may reflect Nassy’s magnanimity, they were law in Pennsylvania.

In a letter from 1795 Nassy wrote of them as part of his family. Mattheus chose not to remain in the United States, returning with Nassy, possibly because he had his own family in Suriname, possibly out of devotion, even affection for his patron and protector.

In 1796, back in Suriname, Nassy proposed establishing a college open to boys of all backgrounds, if they were free, seemingly including non-whites, since Nassy’s prospectus mentions no prohibition on colored applicants.

Davis has added to evidence regarding Sabbath observance when she discovered that a 1707 slave uprising at Palmeniribo, which was adjacent to Jewish plantations, may have had as one of its contributing factors the resentment felt by the plantation’s slaves, owned by non-Jews, that the slaves on nearby plantations owned by Jews had Saturday off as well as Sunday.

Davis also came across “evidence that the rulings of the Mahamad in regard to the cessation of work on the Sabbath and the specified feast days were respected” in the “rare diary of Samuel Bueno Bibaz, manager of a coffee plantation in 1743–1744.”

Although we have little evidence until later in the eighteenth century, Davis infers from the fact that some of the Portuguese Jewish elite of Jodensavanne had the loyalty of many slaves in fighting against the Maroons, both defending against them on their own plantations and also being willing to venture out on sorties against them in the bush, that it “is one of the possible signs of a plantation conducted in a fashion at least tolerable to its workers.”

Wieke Vink has written probably the most important book to date on Jewish Suriname, Creole Jews.27 She has provided the fullest picture so far of the history of the Sephardic community there as a multi-racial society (she also deals with the Ashkenazic community, but I will not treat that here).

With ample evidence from the sources and analysis attuned to communal and colonial politics, Vink explores the ambivalence of white Sephardim toward both slave and free, black and mixed-race individuals.

Vink, who works outside of Jewish Studies, corrects for some of the biases often evinced by Jewish scholars (understanding the latter in terms of institutional and communal subject position), offering a corrective to the continued scholarly lightening of the Jewish settlements’ darker aspects.

Vink describes the twists and turns of a fledgling and vulnerable community, growing in size, power, and wealth, its decidedly non-linear history of inclusion and exclusion of non-whites, its repeated efforts to set boundaries and enforce identity.

She gives us a thorough explanation of the history of Darhe Jesarim (Paths of the Righteous), the study group then congregation of the mixed-race Jews.

Originally established by white Sephardim, who obviously wanted the mixed-race Jews out of their own white congregation, they later essentially regulated it out of existence.

As Vink shows, in the nineteenth century, as creolization and racial mixture increased, the Sephardic community followed suit. In the years that followed the abolition of discrimination “the number of requests by coloureds to be admitted as congregants tripled.”

Between 1830 and 1840, “an estimated 35 to 50 requests were made for the admittance of coloureds or manumitted slaves as congregants in either the Portuguese or the High German community. Moreover, the number of slave requests for admittance increased.” Yet this does not mean race ceased to signify.

Indeed, now that equality reigned within the community far fewer non-whites were accepted.

Her depiction differs significantly from Ben-Ur’s claim that black and mixed-race Jews found admission.

While fascinating and important, the existence and experiences of colored Jews seems to be greatly overplayed by Jewish scholars.

First there is the matter of numbers.

Vink agrees with Ben-Ur that, at least regarding the late eighteenth century, up to ten percent of the Sephardic community was black or mixed-race.

However, she finds that in the nineteenth century this ratio declined to around five percent, a far smaller proportion than existed among Protestants (excluding Moravians), which by then reached an incredible sixty-four percent..

The double face of slavery shows itself everywhere.

Ambiguity, complexity, diversity, all characterized daily life in slave societies; love and loyalty across racial lines, humane masters and whites, slaves and freed slaves assembling and wielding some elements of power over their own lives.

But until abolition, as Hannah Arendt wrote, “slavery remained the social condition of laboring no matter how many slaves were emancipated.”

Samuel Nassy, seventeenth- century community leader in Suriname and son, supposedly kabbalistically- inclined, of active colonialist David Nassy, also allegedly kabbalistically-inclined due to the influence of their teacher Rabbi Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, operated a plantation with close to two hundred slaves.

Davis makes these white Sephardic men the central figures in her meditation on Jewish inclusiveness of slaves.

That seventy slaves ran away from Samuel’s plantation in 1680, that in 1690 an uprising of slaves on another Sephardic plantation saw the slaves killing their owner, does not inspire in me much confidence about the meaning of Jewish inclusiveness toward slaves

In this regard, Davis’s “imagined” Passover Seder in Suriname, at the end of her essay on the Nassy family, disappoints bitterly, turning from her usual analytic rigor to a rhetorical form closer to fiction.

Yes, she wonders whether some of the slaves belonging to Jews might have wished to be back in their own home in Africa.

But regarding the masters, “Some Jewish [slave] owners, reciting ‘The Egyptians treated us badly, they made us suffer,’ may have resolved not to do the same to the slaves on their own lands.”

Note the subjunctive case, but also that only the suggestive positive possibility is offered, not the negative possibility of the kind of compartmentalized mental space so ubiquitous in those slave-dependent centuries among Europeans of all denominations, nor the possibility of utter hypocrisy.

A review of the relevant communal ordinances from around the Sephardic Atlantic will allow us to continue the discussion on another level and address the contradictions I have raised.

Ascamot, Amsterdam:

-

1614: separate section in cemetery established “especially for the burial of slaves, servants and ‘Jewish girls, who are not of our Nation’.”

-

1627: “No black person nor mulatto will be able to be buried in the cemetery, except for those who had buried in it a Jewish mother […] none shall persuade any of the said blacks and mulattos, man or woman, or any other person who is not of the nation of Israel to be made Jews.”

-

1641: Mahamad orders that Sephardic women not send their black and mulatto girls (servants or slaves) to reserve seats for them in the synagogue’s women’s gallery; also that the doors to the women’s section of the sanctuary were not to be opened before six in the morning, in order to prevent the “unseemly” congregating of these women and other servants on the street.

-

1644: “circumcised Negro Jews” were not to be called to the Torah or given any honorary commandment to perform in the synagogue, “for such is fitting for the reputation of the congregation and its good government.”

-

1647: separate section of the cemetery is established for “all the Jewish blacks and mulattos.” Exceptions limited to those “who were born in Judaism, [their parents] having [been married] with quedosim [with kiddushin, i.e., properly, according to Jewish law], or those who were married to whites with quedosim.”

-

1650: “Renewal of the ascama of 1639 which treats the circumcising of goyim. The Gentlemen of the Mahamad declare that the same penalty of herem [the most stringent form of excommunication] [will apply] to any [person] circumcising blacks or mulattos and also any immersing them or [any who] should be a witness for them [as required by halakha—JS], seeing [their] immersing, or [that of] any other person or woman who is not of our Hebrew nation. The Gentlemen of the Mahamad, having some occasion of a son or daughter of a Jew who should come to the [ritual] bath or give birth [?] [and] who should be raised in his house with his [word unclear] may arrange [to do] as he sees fit.”

-

1658: mulatto (and tudesco) boys no longer be admitted for study in the Amsterdam yeshiva of the Sephardim

Ascamot, Suriname:

-

1663 or 1665: the leadership decides to demote the status of jehidim [full members] who marry a mulatta; a jahid [full member] is prohibited from circumcising sons born to jehidim who had been demoted to congreganten. The penalty for doing so is herem.

-

1734: Mulatto Jews in Jodensavanne “may not have any Mitsvahs on Holiday or Sabbath days, but only on rosh hodesh [the New Moon] and the minor fasts and are also required to sit behind the teva [the central table whence prayers were led and the Torah read].”

-

1754: “[S]ince experience has taught how prejudicial and improper it would be to admit Mulattos as jehidim [full members], and noting that some of these have concerned themselves in matters of the government of the community, it is resolved that henceforth they will never be considered or admitted as jehidim and will solely be congreganten, as in other communities.”

-

Members who married a mulatto woman, “either according to our Holy Law or solely in front of the Magistrates,” would have their children considered mulattos by the community as punishment.

-

Non-white Jews had to sit at the bench of mourners, located at the synagogue’s margin.

-

Non-white Jews could not receive certain public blessings (mi-she-berakh).

-

No woman who was black, mulatto or Indian could enter the prayer hall, not even to tend to her master’s children, “considering the Respect of the Holy Place.”

-

By the 1780s the ascamot accept as congregantes any colored children “who carry the name of, or are known to be descended of the Portuguese or Spanish Nation.”

-

1787: further exclusive ascamot, including distinctions between the various categories: karboeger (black and mulatto), mulatto (black and white), mestice (white and mulatto), castice (white and mestice).

-

1794: resolution that jehidim who tried to sit in the seats for congreganten or have congreganten sit next to them in seats reserved for jehidim would be fined one hundred guilders.44

-

1797: jehidim cannot sit at the bench for born congreganten behind the teva and the bench in front of the seat of the samas.45

Ascamot, Curaçao:

-

1702: “women other than the Brides of the Law or of a Marriage, together with their bridesmaids” are barred from sitting “in the front part of the ladies’ gallery” of the synagogue.

-

1751: order “not to bring into the synagogue black or mulatto women in order not to remove the devotion which there needs to be.”

-

1754: lending money at interest to slaves and whites is forbidden, but Jewish law permits taking interest from free blacks.

This list is not fully complete, it leaves out relevant ordinances from Dutch Brazil, London, and elsewhere, while also ignoring de facto practices—such as a door for blacks (Porta dos negros) in the Jodensavanne synagogue—but hopefully it gives a good sense of the sweep of the legislation that blackness engendered in the Sephardic Atlantic.

If these rules revolve solely around the religious congregation, that is because in Amsterdam it was actually the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish community that initiated racial legislation there and they were concerned to create order within their own sphere, while in the colonies the basic racial laws were already laid down by the colonial authorities.

This list makes it easier to see the question of religion and culture in a more precise manner. What role did Judaism play in all of this? What was its relationship to the increasingly racialized societies of the Americas? Here, too, ambivalence and doubleness mark everything. The ordinances waver between halakhic concerns and social/racial ones, as well as between metropolitan and colonial exigencies. In Amsterdam, the metropole, communal leaders found the Judaizing of non-whites undesirable and legislated against it. The first Surinamese ascama did likewise. On Curaçao the prohibition was unwritten. Despite this, Surinamese masters and the community leadership preferred the communal benefits of additional bodies and the psychological rewards of personal procreative self-expansion.

To this we can add what we know of religious factors that do not appear in communal legislation. The very proliferation of mixed-race children shows that Sephardic men were ignoring halakha and rulings forbidding masters to have sex with slave women. With extremely few exceptions, neither community leaders nor rabbis seem to have complained about this or sought to stop it.

Sephardim ceased manumitting slaves according to halakha, now following general secular practice and civil law. Manumission of slaves was rare, and it seems that many individuals and communities in the colonies followed, at least de facto, the halakhic opinion that slaves were never to be manumitted.

In these last three cases, then, “religion” had yielded to or supported common practice that in some sense brought advantage: sexual satisfaction, freedom from the burdens of halakhic regulation of slaves, expanded family, economic gain, extended service from slaves. The one relevant halakha that Surinamese Sephardim seem to have followed is letting their slaves rest on Shabbat, the Jewish Sabbath day.

In short, we must reconsider the conclusion of the great historian Salo W. Baron. He wrote that “Neither the slave trade, therefore, nor slaveholding seems ever to have been so important a factor in Jewish economic life.”

While for Jewish history as a whole he is undoubtedly correct, for the early modern Atlantic world, over the course of two or three centuries several Jewish communities in the Americas depended on and participated actively in the general slave economy. Beyond economics, the presence of non-whites and slaves in a number of Sephardic communities was significant enough to influence communal legislation.

Slavery and race acted together as forces that helped push Sephardim away from halakha and toward secular law and what we now call cultural Jewishness beginning in the seventeenth century.

They functioned as pressures “modernizing” Western Sephardim along an alternative path rather before the Enlightenment, as Yosef Kaplan has discussed. Obviously this particular path of modernization should strike us as paradoxical, if not perverse; yet so it was, as David Brion Davis noted long ago in his path-breaking analysis of Jews and slavery.

Even into the twenty-first century, black and mixed-race Jews have challenged Bom Judesmo for recognition and inclusion, to unfortunately unimpressive degrees of success.

Act of Consolidation, 1854

The Act of Consolidation, more formally known as the act of February 2, 1854, is legislation of the Pennsylvania General Assembly that created the consolidated City and County of Philadelphia, expanding the city's territory to the entirety of Philadelphia County and dissolving the other municipal authorities in the county. The law was enacted by the General Assembly and approved February 2, 1854, by Governor William Bigler. This act consolidated all remaining townships, districts, and boroughs within the County of Philadelphia, dissolving their governmental structures and bringing all municipal authority within the county under the auspices of the Philadelphia government. Additionally, any unincorporated areas were included in the consolidation. The consolidation was drafted to help combat lawlessness that the many local governments could not handle separately and to bring in much-needed tax revenue for the State.

Above: Map of Philadelphia County prior to consolidation

In early 1854, the city of Philadelphia's boundaries extended east and west between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and north and south between Vine and South Streets. Today this area is the Center City neighborhood. The rest of Philadelphia County contained thirteen townships, six boroughs and nine districts; with the Lenape still living all throughout both the city and the county. Philadelphia City's recent influx of immigrants spilled over into the rest of Philadelphia County, surging the area's population. In 1840, Philadelphia's population was 93,665 and the rest of the county was 164,372; by 1850 the populations were 121,376 and 287,385 respectively.

One of the major reasons put forth for the consolidation of the city was the county's inability to govern.

Law enforcement found it difficult to enforce the peace. A person could

break the law in Philadelphia City and quickly cross the border and

escape punishment. Districts outside Philadelphia could not control

their criminal elements and at the same time refused to let Philadelphia

get involved. An example of how poorly law enforcement agencies worked

together was in May, 1844 when an anti-Catholic riot erupted in Kensington. The sheriff was the only police officer available in Kensington at the time and when Philadelphia's militia was called they hesitated because they hadn't been reimbursed for past

calls. By the time the militia arrived, the riot was out of control.

Attempts to improve the issue included an 1845 law that required several

of the surrounding districts to maintain adequate law enforcement and

an 1850 act that gave Philadelphia law enforcement the authority to

police seven surrounding districts. As a result, the act also achieved one of its intended roles: Expand and strengthen the jurisdiction of the Philadelphia Police Department.

The other major reason for consolidation was that Philadelphia's actual population center was not in Philadelphia, but north of Vine Street. Between 1844 and 1854 Philadelphia's population grew by 29.5 percent. Places like Spring Garden grew by 111.5 percent, and Kensington by 109.5 percent. This population shift was draining the city of much-needed tax revenue for police and fire departments, water, sewage, and other city improvements.

The Act of Consolidation, along with creating Philadelphia's modern border, gave executive power to a mayor who would be elected every two years. The mayor was given substantial control of the police department and control of municipal administration and executive departments with oversight and control of the budget from the city council.

Districts, townships, and boroughs consolidated into Philadelphia

The following is a list of municipal authorities which were consolidated into the modern City and County of Philadelphia.

Aramingo Borough; Belmont District; Blockley Township; Brideburg Borough; Bristol Township; Byberry Township; Delaware Township; Frankford Borough; Germantown Borough; Germantown Township; Kensington District; Kingsessing Township; Dublin Township; Manayunk Borough; Moreland Township;

Moyamensing District; Northern Liberties District; Northern Township; Oxford Township; Passyunk Township; Penn District; Penn Township; Philadelphia City; Roxborough Township; Richmond, District; Southwark District; Spring Garden District; Philadelphia Borough; Whitehall Borough

DVPASCPFFP Actions and Goals

Provide a platform that empowers members to do the necessary internal work to advance the coalition.

Serve as a coalition resource hub and support system for members

Develop systems and accountability to ensure coalition is centered throughout the Coalition’s work

Identify and advocate for state and federal policies that address environmental justice

Identify and address gaps in representation of our membership and partnerships

Create synergy with coalition efforts across the watershed to identify gaps, and reduce duplication and overburdening

Address internal structure, develop a coalition lens, and create a 3 year actionable road map with Advisors and Consultants